Is the Vise Dead?

Even though it has been around forever, does the vise have limitations for shops in a competitive marketplace? Do you need to reinvent the wheel to reduce some of its limitations? To evaluate the vise’s viability in today’s manufacturing operations, we need to uncover the most efficient way to apply it.

The vise is the most ubiquitous piece of workholding equipment. I see them in facilities serving just about every industry, from aerospace to medical. They are versatile, rigid and reliable, don’t consume excessive volume and have been around forever. All that being said, the “it’s how we’ve always done it” argument doesn’t hold water for shops in a competitive marketplace – or for operators, machinists and the like in hope of advancing their capabilities for that matter. In order to evaluate the vise’s viability in today’s manufacturing operations, we need to uncover the most efficient way to apply it. Let’s break down how the vise is used today.

When it comes to workpiece size, you can just about rule out large parts because of the limited throat opening, generally six to 10 in, based on the manufacturer. But the combination of rigidity and flexibility with quick and relatively easy locking and unlocking (once it’s already set up) still make the vise a good choice for what most would consider small to medium workpieces of the appropriate shape and form factor. The vise is effective for prismatic workpieces because you can grab them from two sides with no preparation of the part or raw material. Round workpieces, on the other hand, are better served by a lathe or a chuck jaw. Additionally, once any machining is done to a part, holding on to cut faces can be limiting if the part is thin or easily deformed; you don’t want to clamp onto it from the outside. You want to hold the part with some level of control, usually with a dedicated fixture. Vises are particularly useful for initial operations, however, they more cumbersome and risky on late-stage machining.

In terms of production volume, vises don’t work very well when batches are large. Instead, dedicated fixtures and machines tend to be more efficient because setups don’t change. That brings us to changeover. We’ve established that changeover barriers make vises unsuitable for high production work, but the vise also has proven inefficient when working with small parts. The smaller the workpiece, the faster its individual cycle and the more particular its workholding location becomes. For example, if it takes two to five minutes to run a small workpiece and 30 seconds to change, that’s a huge – and costly – percentage of that part’s cycle time. At this point, the fixtures are usually designed to handle multiple parts to spread the changeover time. With large parts out of the question, medium parts, with cycle times of 20 to 30 minutes or more, appear to be the sweet spot for vises.

Now on to initial setup, one of the areas where a vise can eat up a lot of time. Taking a raw workpiece, setting the zero point and end stop, then running the program is all fine and good. It’s when a new batch of parts comes into play that the vise’s limitations emerge. Every time you change to a different series of parts, the zero point change often requires significant time to reestablish. What’s more, switching from vise work to fixture work can be a bear. From cleaning the table to getting the new workholding square and true, eventually you reach a point of diminishing returns – that’s real money – where the operator can’t change the product fast enough. So, without further ado, it’s time to answer the question of the day: is the vise dead?

No, the vise isn’t dead. It’s a tried and true piece of workholding that’s still useful for most general machining applications. However, considering some of the limitations discussed in the areas of part size and shape, setup, productivity levels and changeover, I have an idea for how to give your vise a more fulfilling life.

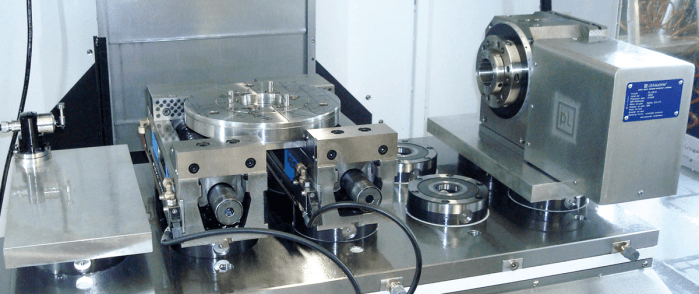

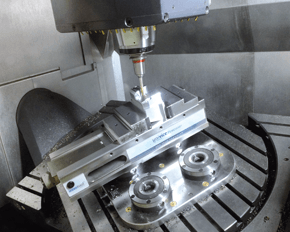

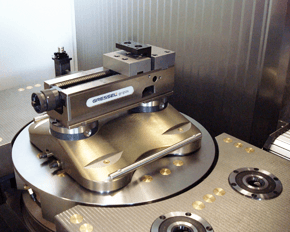

In scenarios where you’re not 100 percent dedicated to a certain type of production, you need to have the flexibility to adapt between prismatic raw workpieces and fixtured workpieces. That’s where a zero-point workholding system shines. If you go into any of our end users that have adopted our UNILOCK system, you’ll see vises either on an adapter plate or with clamping knobs attached to the bottom of them. While we do sell vises preloaded with UNILOCK knobs, many vises can be adapted fairly easily. This approach solves nearly all the setup, changeover and production challenges I addressed earlier. Each vise manufacturer is different. Those that have flat and uniform bottoms make it easy to add knobs. Others may already have locating features (not all patterns match ours) on the bottom that make it even easier to add knobs. If a vise is cast, they are not always flat and uniform on the bottom, making it impossible to install knobs.

There’s also a creative alternative that meets somewhere in the middle of converting fully to zero-point and sticking with legacy vises: I often see setups with a standard vise on one end of the machining table and a UNILOCK chuck on the other. While these setups don’t realize the full benefits of zero-point workholding, it is a nice compromise. Does the vise have its limitations? Yes. Is it dead? No. Do you need to reinvent the wheel to reduce some of its limitations? No. Simply combining what the vise is best at with what zero-point is best at can result in serious time and cost savings.

Did you find this interesting or helpful? Let us know what you think by adding your comments or questions below.